The Politics of Protection

REACH Community Development’s federal lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security is framed as an urgent response to alleged reckless use of chemical agents near Portland’s ICE facility.

But residents living in the building at the center of the dispute say the organization failed to protect them when disruption and danger was real and ongoing, and that they only acted once the conflict could be elevated into a national political fight.

“A lot of people in the building are angry,” said Cindy, a REACH resident who lives beside the ICE facility. “They’re not doing this for us. It’s a bunch of BS. It’s just PR and political stuff. It’s a political stunt.”

Another resident, who wished to remain anonymous, told me: “I was trying to get come back to my apartment, open the front door, and I had like, a crowd of people, like eight people just come by and pull my hair and stuff like that. And I don’t know why. They’re all wearing masks. And the police couldn’t figure out who the person was.”

The lawsuit asks a federal judge to halt DHS’s use of tear gas and chemical agents, alleging they were deployed “to put on a show for conservative influencers.” It also claims federal officers intentionally targeted a resident’s apartment while she livestreamed protests from her window.

Residents say that isn’t true — that dhs was responding to riots and dangerous, illegal behavior by protestors. they say concern for their safety was notably absent when they sought help through local channels.

“When residents sued the city to enforce the noise ordinance, REACH wasn’t even part of it,” Cindy said. “They didn’t care.”

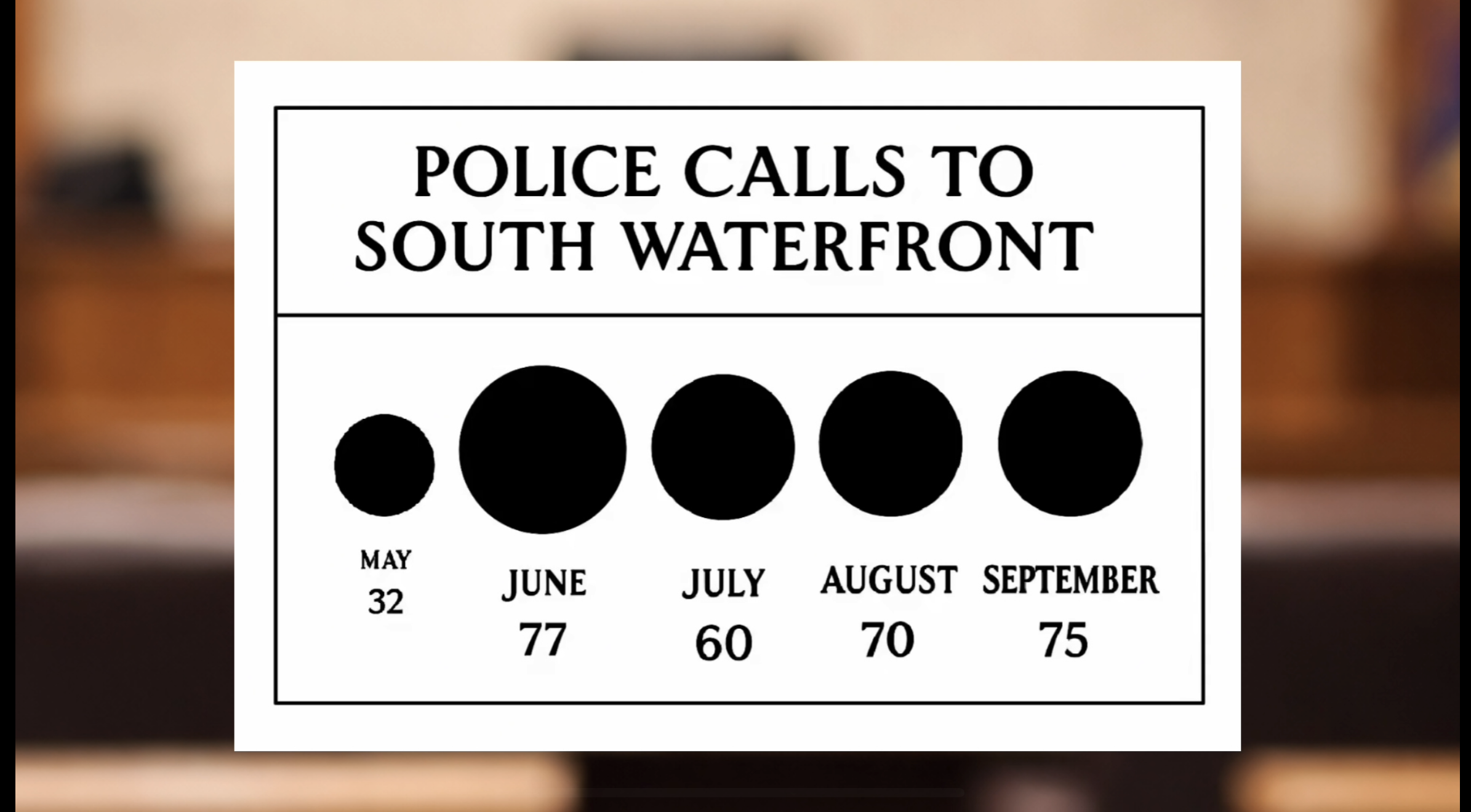

According to Portland Police call data, between may and June, calls for service in the area surrounding the building increased by roughly 150 percent. Arrest records from the summer and fall include multiple violent incidents, including crimes involving REACH residents.

“It feels like the buildings become like a political purity test that you have to pass or something,” the anonymous resident said. “And if you’re neutral, it’s not welcome.”

Nighttime protests — which residents describe as the most disruptive — involved sustained crowds, amplified noise, and repeated disturbances documented through police activity and livestreamed footage.

Despite those conditions, residents say REACH did not intervene.

“We reached out to management for help with the noise, and they didn’t care,” Cindy said. “They said it wasn’t in their scope.”

Residents also say REACH never requested police action to address multiple long-standing encampments used by protestors immediately outside the building, even as safety concerns escalated.

“They never asked police to clear the encampment,” Cindy said. “There was a twenty-gallon propane tank and a heater right next to the building. If I did that, I’d get written up. But they wouldn’t do anything.”

Rather than pursue local enforcement or mitigation, residents reach say escalated the matter directly to federal court, framing DHS’s actions as politically motivated and performative.

“That idea that tear gas was used for propaganda is BS,” Cindy said. “They were using it because protesters were cutting power cables, busting out windows, spitting on officers, and bringing a guillotine to the ICE facility. You can only put up with so much.”

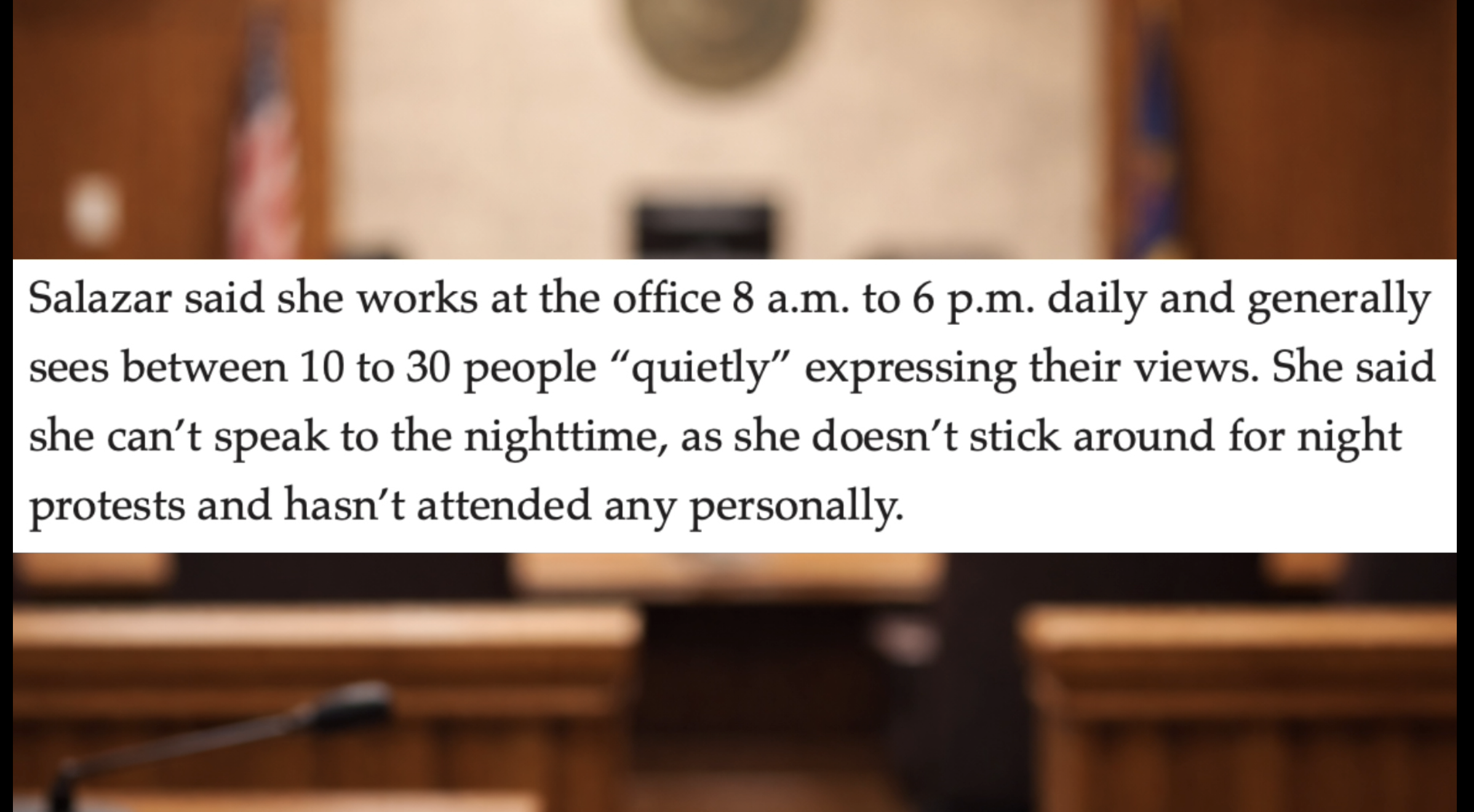

In an interview with The Oregonian, REACH community development CEO Margaret Salazar said she typically sees “between 10 to 30 people quietly expressing their views” during the day, but she acknowledged she doesn’t remain for nighttime protests.

Residents say those nighttime hours were precisely when they felt most vulnerable.

“The only time I feel safe coming outside is when there’s a visible presence that isn’t black bloc,” Cindy said. “That’s the truth.”

“I’d like them to come in this neighborhood and stand here for a night and see what it’s like,” the anonymous resident said.

Salazar’s professional background places her deeply inside federal housing policy and advocacy networks. Before becoming CEO of REACH in late 2023, she served on the Biden–Harris transition team reviewing the Department of Housing and Urban Development and later held senior appointed roles within HUD, including as Regional Administrator for Region 10. She also serves on boards of national housing finance and policy organizations connected to federal funding ecosystems.

REACH relies on millions of dollars in federal housing funding, placing it in the unusual position of suing one federal agency while remaining financially dependent on others.

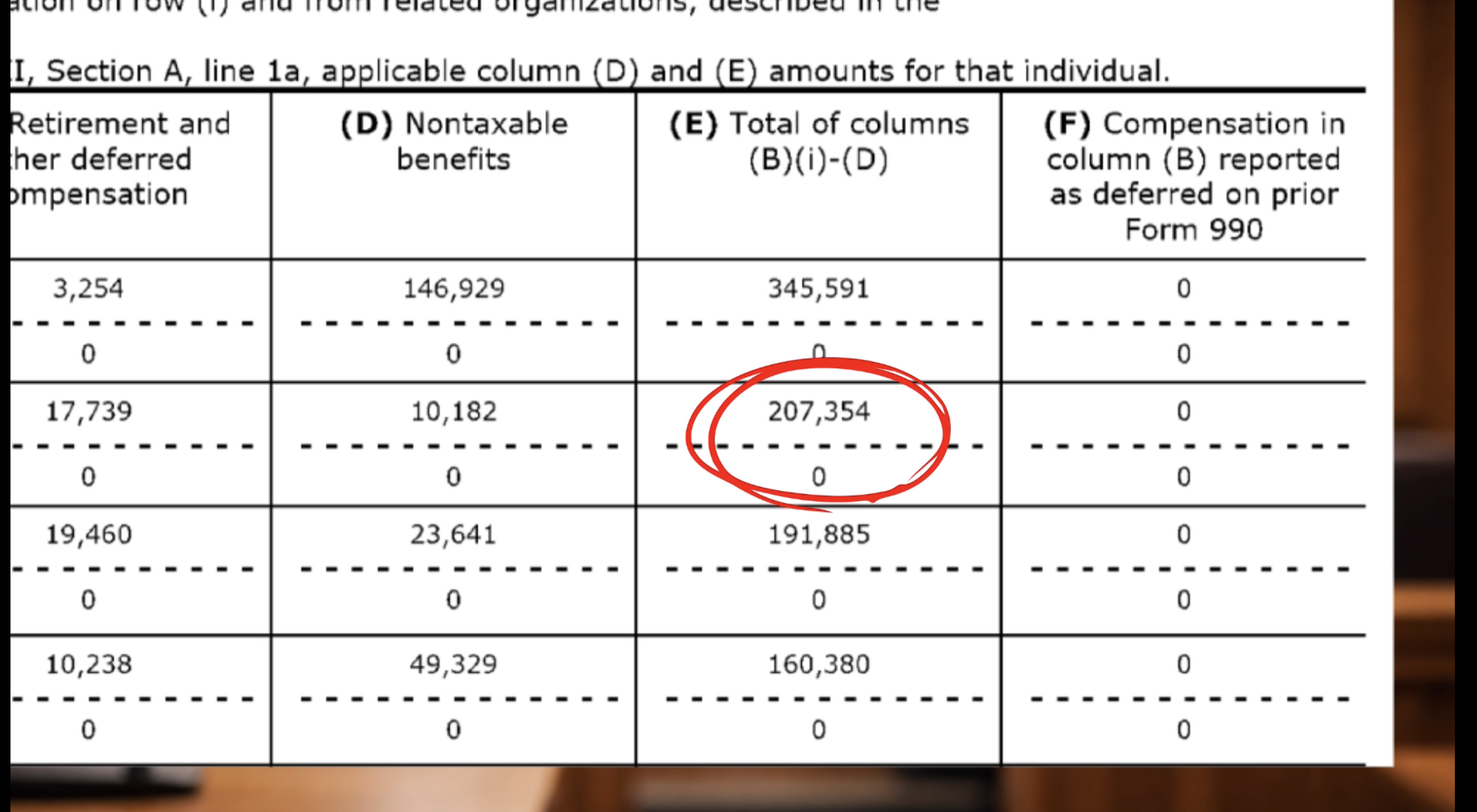

Public tax filings show that executive compensation at REACH has historically been in the six-figure range.

According to the organization’s most recent publicly available IRS Form 990 filings, CEO compensation prior to Salazar’s tenure ranged from approximately $179,000 to $207,000 annually between 2019 and 2022, including base pay and reported benefits. Salazar became CEO in late 2023; her compensation will not be disclosed until REACH files its 2023 or 2024 return.

Residents say that context helps explain the organization’s priorities.

“It’s very obvious the residents don’t matter to REACH,” Cindy said. “What matters is politics.”

According to Cindy, REACH’s response to months of disruption was minimal.

“They gave us earplugs,” she said. “That’s it. That was the solution.”

Residents say the lawsuit feels less like protection and more like theater.

“They’re playing stunts with our lives,” Cindy said. “They’re trying to look good for the city council and the mayor. They’re not fooling anybody.”

REACH and Salazar were contacted for comment regarding why the organization did not pursue noise enforcement, encampment removal, or increased police presence during the period when calls for service and violent incidents surged.

No response was received by publication time.

For residents living beside the ICE facility, the issue is not abstract. The lawsuit targets actions taken by Trump-era federal authorities, brought by an organization now led by a former Biden administration housing official. But residents say their safety concerns went unanswered when the disruption was ongoing — and only became urgent once the conflict could be reframed as a political case in federal court.